I was still a little bleary eyed as I crawled out of the back of my Jeep. Our camp, on the shore of Longue Pointe, was still quiet. We were a lonely arrangement of Jeeps on the rocks above the receding morning tide. A few of the team were just getting started with breakfast and coffee. The sound of gravel and tires faded into the calm morning sounds. I looked up to see Jimmie’s truck slowly round the curve. “Wow”, I thought, “he is early”. It was 0630 in the morning. When we had talked during our awkward negotiation the day before, we seemed to settle on 8 am or 9 am. Jimmie said he would find another freighter canoe guide and meet us where we camped in mid-morning. He was early.

I slowly walked through the wet weeds to the gravel road, still a little sleepy. The air was fresh, chilled, and a little damp. The sun was new, and the light was dim. He slowly rolled to a stop with his window down and starred at the canoes lined up just down the hill. Without looking at me, he put his truck in park, opened the door and stepped out. I search his face for some meaning. He continued looking downhill.

I said, “Hey”.

He nodded, still looking away – this time at the quiet ocean. He seemed to be sizing everything up.

“I thought you said between 8 and 9.” I said, trying to cover for the fact that we weren’t ready.

“Wind. . . Tide . . . good. We go now”, he said with a nod to the ocean. I paused.

“No second canoe?”, I inquired.

He smiled a slightly crazy smile. He glanced at me with slightly crazy eyes, “I couldn’t find anyone who wanted to go.”

He kept his crooked smile, then looked away. This was rare for him to smile at me. It seemed like he was implying that we were crazy for going, but I gave up trying to read this man. We seemed worlds apart at times, yet we seemed to understand each other. Our relationship wasn’t something I could figure out right now. It was what it was.

Knowing that we had 10 people and only 5 -6 could ride in a canoe, I started to think of a way to ask him how this was going to work. I started by saying, “So. . . “

He immediately said, “Two trips.”

“OK”, I said. “We get ready.” I hesitated, wondering if I (actually) just said that sentence without the needed verb. He nodded, still starring at the boats at the bottom of the hill. I started turning to walk away. I followed his gaze down to the boats to see if there was a polar bear or something important. Nothing. It wasn’t awkward anymore to have him always stare off into the distance while we were talking. Jimmie just wasn’t the kind of guy to waste words. I liked that about him.

We gathered at camp, everyone had a curious look. I told them the news about only a single canoe. We had doubts that a second trip would be possible. We discussed who would go on the first trip. I was a little optimistic that if we hurried on the first trip, would could make it back in time for a second one. At 35 miles per hour, we could cover the 70 miles in two hours, spend 30 minutes on site, then return by noon or 1 pm for the second round. I would find out later that I was wildly optimistic.

We chose the first group. AR, Loveboat, Hot Pockets, Dinty and myself. They had been with the team the longest and contributed the most to the team. I hesitated with the decision and tried feebly to give my spot up, but they insisted. They knew that I had planned to reach Cape Jones for more than a decade and a bit of family spirit was involved. To this day, I have a deep appreciation for Bones, Reroute, Napa, Yellow Cake and Dudley for their unwavering kindness.

After we gathered our gear, we walked down to the gravel beach where over 60 freighter canoes were lined up, waiting for another voyage on James Bay. Jimmie had a small generator charging a sat phone. I looked around to see how prepared he was.

I was impressed. He had a PFD, Sat Phone, rescue gear, a radio (he kept radio contact the entire trip), a shotgun, warm clothing and more. He was more prepared than I expected.

He was busy arranging 7 large fuel cans. He moved gear and rearranged cans. We helped without instruction or any conversation.

Then, without saying a word, he reached into the back of this truck, pulled out 6 half pipes and dropped them on the gravel behind his 24’ canoe. A 60-horsepower motor hung from the transom. It was old and the prop was pretty dinged up. I swallowed as I walked around to the other side. Without saying a word, Jimmie positioned himself on the canoe and began pushing it to the water. Finally realizing what he wanted to do, we quickly grabbed the gunwales to help.

We slid the canoe closer to the water by about six feet. Jimmie picked up a half pipe from the front, walked to the back and dropped it. We pushed again for another 4 feet and repositioned a half pipe. After almost a dozen of those maneuvers, the boat was floating. Jimmie loaded gear without any conversation. We loaded our gear, climbed in and positioned ourselves in the seats. The last piece of gear, a cased shotgun, was loaded and then Jimmie loaded his truck and drove away to park it.

When he returned, he pushed us all further out into the water, then climbed in. He fiddled with the motor for a couple of minutes occasionally pulling the cord. The rest of us used the hand carved paddles to move slowly from shore. Then, the motor roared to life. The canoe shook and vibrated. With a clunk we were in reverse and slowly backed away from shore. Bones and Reroute followed in their kayaks while Dudley, Yellow Cake and Napa looked on from shore. With another clunk we came about to starboard. The canoe shuddered, I positioned myself at the bow of the canoe expecting a rough but exciting ride. This is it, 70 more miles and we finally reach our goal. 35 gallons of fuel and 7 tank changes and we will be back from Cape Jones. I was excited.

Cape Jones is a bit of a mystery. It is one of those places that has very little written history. The name “Cape Jones” was given by the English sometime in the 17th century. In 1961, the cape was renamed Pointe Louis XIV. Which is interesting, because most the people that live within 300 miles have no idea it was renamed.

It is a long rocky point that that stretches into the sea, marking where James Bay and Hudson Bay meet. It is a treeless landscape consisting of rocks, pebbles, windswept lichen and wet depressions.

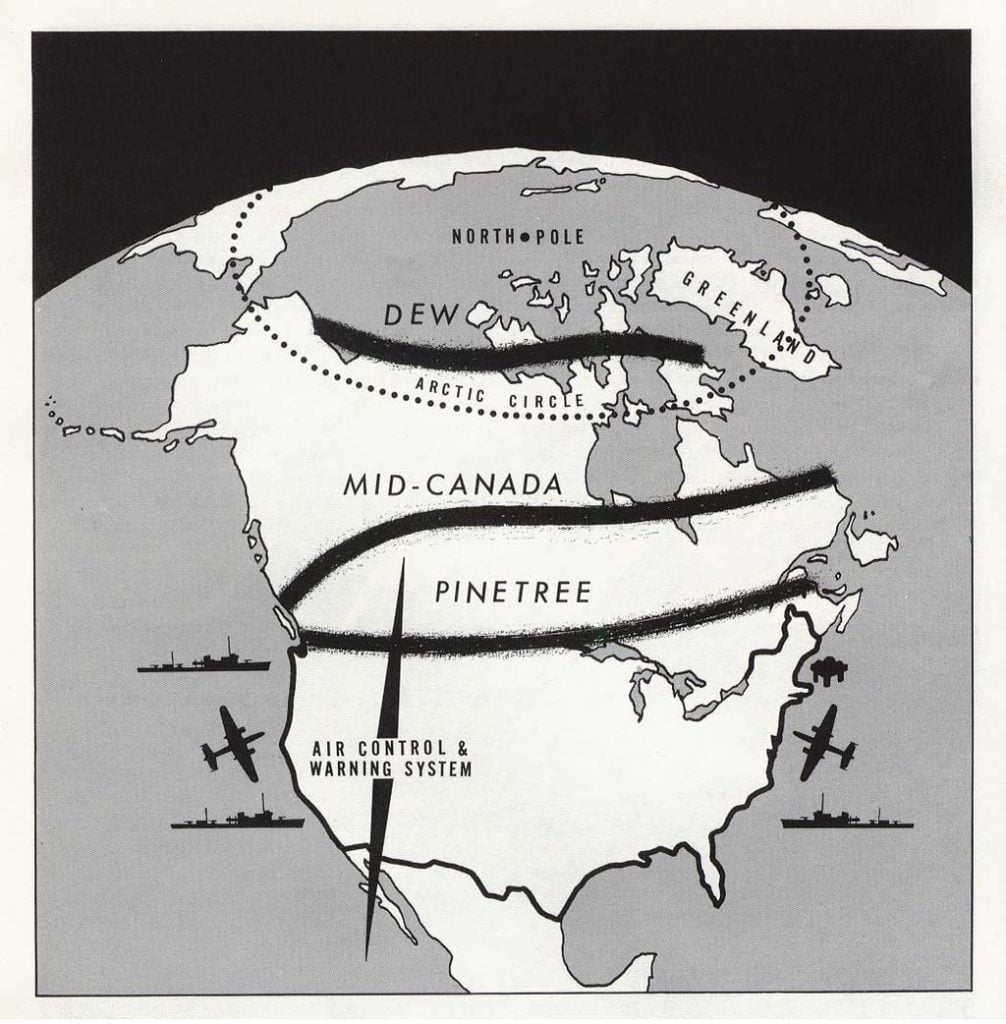

In the middle of the cape is MCL Site #410. The site is an abandoned Royal Canadian Air Force base. It was built, operated for a few years and promptly abandoned. It was a communication relay site for the “Mid Canada Line” during the cold war. The Mid-Canada Line (MCL), also known as the McGill Fence, was a line of radar stations and communication sites running east-west across the middle of Canada at approximately the 55th parallel. Its mission was to provide early warning of a Soviet bomber attack on North America. It was built to supplement the less-advanced Pinetree Line, which was located further south. Most of the Mid-Canada Line stations were used only briefly from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, as the attack threat changed from bombers to ICBMs. As the MCL was closed, the early warning role passed almost entirely to the new, more capable DEW Line further north – near the Arctic Circle.

We motored north through a maze of rocky, treeless islands. Jimmie would expertly maneuver through shallow passes with just a few inches between the hull and rock. He would lift the motor, glide over a line of barely submerged rocks, then drop the motor and accelerate. He would then position the tiller between his legs to steer. He was stoned faced behind his sunglass. He kept his hands in his pockets as he surveyed wildlife and the harsh shorelines. He stood almost the entire time, steering with his legs.

The air was chilly, the wind was cold. I was behind the upswept bow, mostly protected from the wind. Farther back, without the protection of the bow, AR, Dinty, Loveboat and Hot Pockets felt the chill. Even with a dry top and emergency blankets to block the wind, it was cold.

Riding in the bow was rough. Within 15 minutes, our course took us directly into the waves. The prospect of trying to sit was akin to riding a mechanical bull. Instead, I stood with a slight squat grasping the gunwales. This proved much more comfortable for the first hour. But as the first hour became the second, then the third and progressed into the fourth hour, I began to dread the next day and the sore muscles I would experience.

We passed many geese. As we got close, they would lay flat on the water to hide behind the waves. At times, Jimmie would turn to make his approach between two islands. The geese would then flap and waddle, their little webbed feet kicking, and they would take flight to escape.

At one point, a small seal was sunning herself on a rock. She looked at us, with huge eyes. Then dove into the water. A minute later, her head popped, much closer to us and almost 150 yards from her original perch. She seemed curious and kept following us until our speed and direction took us out of sight.

After an hour, we stopped at a small rocky island. Jimmie talked on his radio in Cree. I hopped out with the rope. He threw two fuel containers out. Then he crawled out to mix fuel with oil. He did this a couple of times. He worked hard for us and we never knew what he was planning, why we were stopping, or why we were turning.

At one point, I looked back to notice he had left his position as stern sentinel and was rearranging gas cans. He disconnected the engine’s fuel line from one can and connected it to another while the motor hummed on. Other times, I would try to understand how he was navigating dozens of miles of uncharted water. At times, I could see his aid to navigation. A lone stick with an animal skull or a part from a shipwreck would be carefully stacked on an island knoll. He would take a heading straight at it. He would promptly turn and a few seconds later I would spot a cairn set up on another distant island. It was impressive.

We passed a couple of camps the size of small villages. Unmapped settlements that stood in hard contrast to the lonely landscape. Occasionally, Jimmie would chat with someone on the radio. During one transmission, he spoke in Cree and I suddenly recognized the words“Cape Jones”. There was a long pause on the other end, then suddenly, “Ouwah, Ouwah Ouwah!”. Which is a Cree expression for “WTF” or an enthusiastic expression of “WOW”.

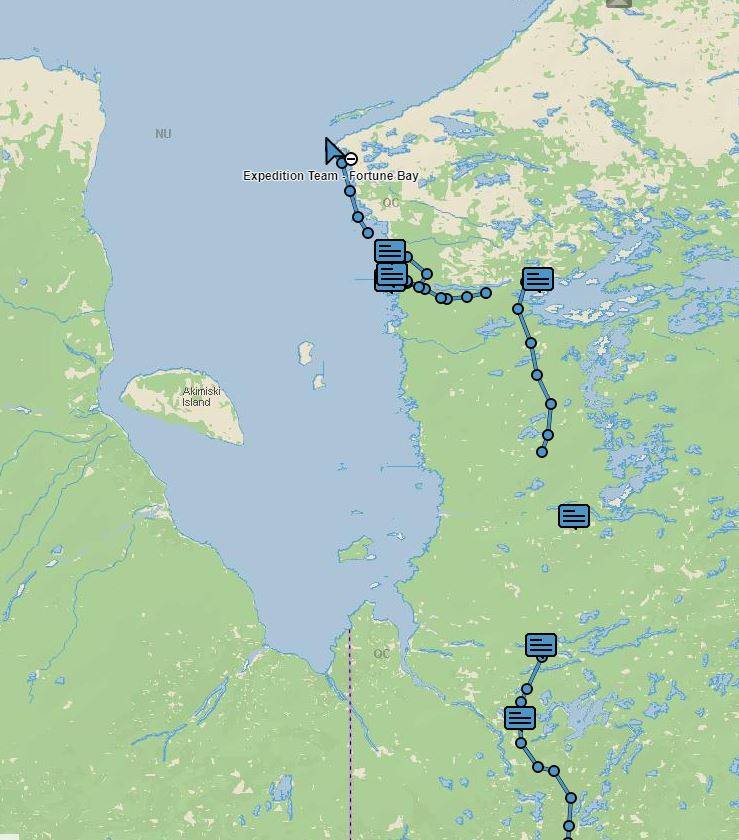

I kept track of our progress on the satellite tracker and it was painfully slow. Since we left at low tide and into the wind, progress was extra slow. We had to avoid obstacles that were only dangerous during low tide. We were still over 15 miles from the cape after 3 hours.

Finally, we made the turn west in view of a small village. Jimmie brought us to the shore of a small island. A snowmobile and sled were perched on a lonely ridge. The team all disembarked and scrambled over the ridge for a much-needed bathroom break. Jimmie measured oil and filled a new gas can.

“Cape Jones, not long.”, he said as he loaded the tank and fuel can back into the canoe. Shortly after we left, with about 8 miles to go, we rounded a point and immediately spotted the imposing antenna arrays at the cape. They were small at that distance, but striking as they languished in the haze. These arrays had their anchor bolts cut more than 50 years ago during decommissioning. It was assumed that the wind would easily topple them. But there they were, still suffering the elements, unwavering, more than half a century later.

For the next 20 minutes we moved closer with the cape slowing growing. The wide expanse of open water was still rife with submerged obstacles and we would occasionally slow down.

With 3 miles to go, we spotted the Cape Jones hunting camp and a couple of small buildings on shore at our destination. Finally, we closed in on our landing site near a small cabin. Jimmie cut the motor and we drifted, I finally jumped out with the rope, we had landed. We secured the canoe, Jimmie unloaded some gear.

He looked at me and said, “What do you want to do?”

“Stay a bit. Look around, walk to the towers”, curious to know if that was okay.

“You take pictures, walk around. I’ll have lunch.”, he said.

With that, he busied himself, hauling gear to a sheltered area among some rocks and lichen. I quickly started hiking toward the towers, just over a rocky knoll. We all split up for our own silent exploration.

As I passed the small hunting cabin comfortably nestled in the hill, a raven the size of a small child sudden stumbled off a small cabinet at the back of the building. He was surprised to see a human. His wings flapped as he regained his balance and he took flight. Being of Viking stock, this was a treat. He flew to the top of the knoll, landed on a rocky perch and kept watch over me. I imagined that is was Huginn or Muninn (Odin’s Ravens) looking over me.

The hike was treeless and expansive. The raven stayed behind, statue-like with his feathers waving in the wind. He didn’t move from his perch for an hour. The towers dominated the landscape. The only sounds were the wind and another bird. This bird was very angry and seemed supremely disagreeable with our presence. He screeched every few seconds and circled as we walked across taiga, huge boulders, wet moss, rusted drums, pieces of rusting equipment and other assorted items. It was sad, but interesting at the same time.

We explored the buildings. The were disintegrating. The steam pipes were broken and shattered, ceilings were hanging, and walls were falling. I carved our team initials and date in the last of the drywall in the control building. We were one of a dozen who recorded their visit. The lack of man-made noise was astounding.

Everyone was quietly exploring the buildings, pools, tanks and equipment. All alone, with nothing to say. The sun was bright the wind was gentle and steady.

We began our amble back. We had reached Cape Jones. It was amazing.

Author’s Postlogue: Unfortunately, even though we had planned for the rest of the team to travel to Cape Jones the next day, the weather was too extreme. We found Jimmie the next day in a small restaurant. We intended to settle-up. He was surprised that we compensated him.

As I handed him a roll of money, he asked “what’s this for?”

“For taking us to Cape Jones”, I replied.

He stuffed it in his pocket, nodded and walked away. We met him one last time on that expedition. He was talkative and friendly – very out of character or maybe that was who he really was. I thought, maybe we were actually “friends”.

At the end of the expedition, we ended up in the commercial center waiting for an overly energetic Cree to make us thatched geese. His name was Darcey and he was insistent that we wait for him to sell us some. The local radio station asked for an interview. More people wanted to meet us. Some asked us not to go. But, we had to go. We left on a Thursday, headed back down the James Bay Highway. We stopped for a selfie at the Chisasibi welcome sign. We needed to head home. We accomplished a lot.

I returned to Chisasibi in the fall on the Trans-Taiga Expedition. I spotted Jimmie in a parking lot. I walked over and said, “Jimmie!’ He smiled grandly. We shook hands. We both looked off into the distance. We talked a little. Then we turned from each other and, this time, we both walked away. . . without a word. I understood now.

Written by Chuck Hayden