Thump-thump…clank. Every few seconds we would hit a full width trough in the payment and the Jeep would jump, followed by the tinkle of metal objects – coins, a spoon, tent stake – somewhere in the vehicle. On occasion an object would slide off its perch and dive gracefully into the crevasse between the seat and console forever lost somewhere in the vast under seat collection point – the vehicular equivalent of the Bermuda Triangle. It was also a little unnerving to spend hours driving in this condition. Each of us started to worry about our vehicle and the constant pounding it was suffering. Not to mention the stiff neck and besieged spinal column.

We were on the James Bay Road in Quebec around Kilometer 365. It was the second day since leaving New Liskeard, Ontario and we were into our fifth hour of driving this lonely road (third hour of day two). A convoy of 9 vehicles hopping along at about 95 kilometers per hour. The radio had been relatively quiet since we left our camp at Lac Rodayer.

Then the radio crackled with a confusing “ohhhhh” and a few seconds later, “Pathfinder, Yellow Cake just lost a wheel. . . “

“That’s not good”, I replied. I noticed the road behind me was empty. I turned the vehicle around to see the damage. As I approached the white Nissan, I spied Kevin (Yellow Cake) rolling his recently departed wheel from the ditch on the opposite side of the road.

There it was. . . a reasonably epic situation. We were on the most remote road system in North America. A tow or repair in this part of the world would be very expensive and could take a couple of weeks. We didn’t just have a flat tire, but one of the most important parts necessary for motion just departed the vehicle and flew across the road.

Our first step was to analyze the situation and take inventory. Upon the initial inspection, there were no broken lugs. They were all clean. The nuts just “worked themselves off” and the tire bounced across the road. Piece of cake to fix . . . if we had spare lugs. If we could also get the vehicle elevated high enough to reinstall the tire. The broken shock might be important, but not necessary.

Well, it just so happened that Doug, had 5 spare lugs nuts. This and his uncanny ability to provide any requested part for the expedition earned him the name “Napa”. . . after the auto parts store.

After some creative jack work with multiple jacks offered by other expedition members, and a little digging in the shoulder of the road, the vehicle was elevated. While we worked, the rest of the expedition took some time to tighten their lug nuts. The tire was installed, Yellow Cake lowered his vehicle, did some testing and we were off.

This was day two. We had travelled 787 kilometers (489 Miles). We started in New Liskeard, Ontario at a small lakeside park in an unassuming farming community of northeastern, Ontario. The first hundred kilometers brought us through farming communities and into Quebec. By kilometer 200, the farms gave way to mines and the distance between towns stretched out. By kilometer 412 we reached Matagami, Quebec. This was the end of civilization. It was kilometer 0 of the James Bay Road, where hundreds of wide eyed travelers begin to accomplish one of their “bucket list items”.

At Kilometer 0, there is an infamous “check point”. The purpose of this checkpoint is interesting and a little elusive. You have to give your name either through a loudspeaker or by going in to a mobile building. This is most often done dutifully. Cars stop at the speaker, give their name, wait for confirmation and then drive off. Curiously, I’m not sure why.

We chose to enter the building to “check in”. This building has some tourist items, maps and guides for the James Bay Road. Internet accounts from travelers who have stopped at this checkpoint can be dramatic. Many claim that you have to be “interviewed” or checked for your ability to survive the long journey ahead. Reading these accounts online give you the impression that there will be uniformed personnel with spot lights, German Shepherds and the suspicious eye of a disciplined officer.

The truth is, you can give them any name you’d like. They have no way of knowing where you’re going, when you will arrive. They don’t question if you are ready for the journey. They are busy passing out maps, guides and taking down whatever name they are given. We gathered in the building and stood in quiet disappointment. The attendant awkwardly handed out map books, answered a few questions and waited for us to leave. He did take down our names with a sort of somber seriousness. I gave the name “Richard Tracey”, corrected the spelling as he scribbled and awaited some sort of alarm or a few men in suits to enter through one of the many doors in the lobby. But, no one cared. So we were off for our bumpy ride north on the James Bay Road.

The James Bay Road was born in June of 1971, when the aptly named engineering firm Desjardins, Sauriol and Associates met with government officials in Matagami, a small mining town located 400 miles south of Chisasibi. The firm was tasked with the construction of a basic road to the future Radisson site and the Cree settlement at Fort George. The deadline was 450 miles in 450 days, an ambitious timeline for sure.

Teams of land surveyors, engineers and lumberjacks were deployed by seaplanes and helicopters to clear a path for a permanent road. Parallel to the path, a few kilometers away, an ice road was first built to move heavy machinery north.

This was an immense undertaking. The 450 mile road would be one of the most remote roads in North America. If the road were built from Grand Rapids, Michigan, it would reach Lexington, Kentucky. Actually, they were building an ice road too. These two roads together, if built from Ann Arbor, Michigan, would reach Tallahassee, Florida. All this with no hotels, no gas stations, no towns. . . nothing but swampy, rocky wilderness. All in 450 days.

The James Bay Road is desolate. There are a few turn offs and 6 access roads that eventually lead to villages along the entire 620 kilometers (388 miles). The road is paved, though it can be very rough at times.

At kilometer 381 (the road is defined by kilometer marks and not place names), there is a single gas station called “Relais routier” or “Roadhouse”. It boasts a busy cafeteria and a garage that is mostly unhelpful and without any basic parts, such as lug nuts. There is lodging available and a few other services. The three gas pumps are strategically hidden behind a building and are usually inadequate for the amount of traffic waiting to fill up. The cashier is perpetually juggling multiple bills from a confusing array of travelers who have moved their vehicle, grabbed a meal, then stood in line for twenty minutes. All while a host of other travelers have also filled up.

The official language of the Roadhouse is a combination of French, English or sometimes Cree. These are all spoken at random as you try to guess the native language of the person you are speaking to. The staff is fluent in both French and English and even switches back and forth in the same conversation. Generally, the place is very busy, and is efficient in a curiously chaotic way.

After the gas stop, we began the last 259 kilometers of a spine jarring drive to a town called Radisson.

The rest of the James Bay Road was filled with more desolation. The trees became shorter and evidence of forest fires dominated the landscape. Bogs (called Muskeg) grew more prevalent and you could see intermittent evidence of subarctic flora. Two hours after leaving the gas stop, we spied a powerline slowly moving closer from the west. We passed an airport, which seemed to be dropped off the back of a semi and left in the wilderness. Finally, we approach an intersection of two paved roads. One road quietly led east to Chisasibi and the other continued northeast to our first stop, Radisson and the “big dam”.

Upon entering Radisson, you will notice the multi-level hydro company buildings immediately. It was built as a company town in 1974 to accommodate workers for the James Bay hydroelectric project and named after the 17th-Century French explorer and founder of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Pierre-Esprit Radisson. In 1977 when construction of the dams was at their peak, Radisson had a population of about 2,500. Today, the town hosts about 300. It is decidedly a destination for the non-native tourists as it caters to outdoor sports tourism, such as hunting, fishing, and camping.

Even though Radisson is a remote town (hundreds of miles from any small city), it has a few comforts for those used to civilization such as two fuel stations, hotel, motel, campground (summer only), a general store, restaurants, gift shops, a school and a hospital. It also has an abundance of power lines in the area.

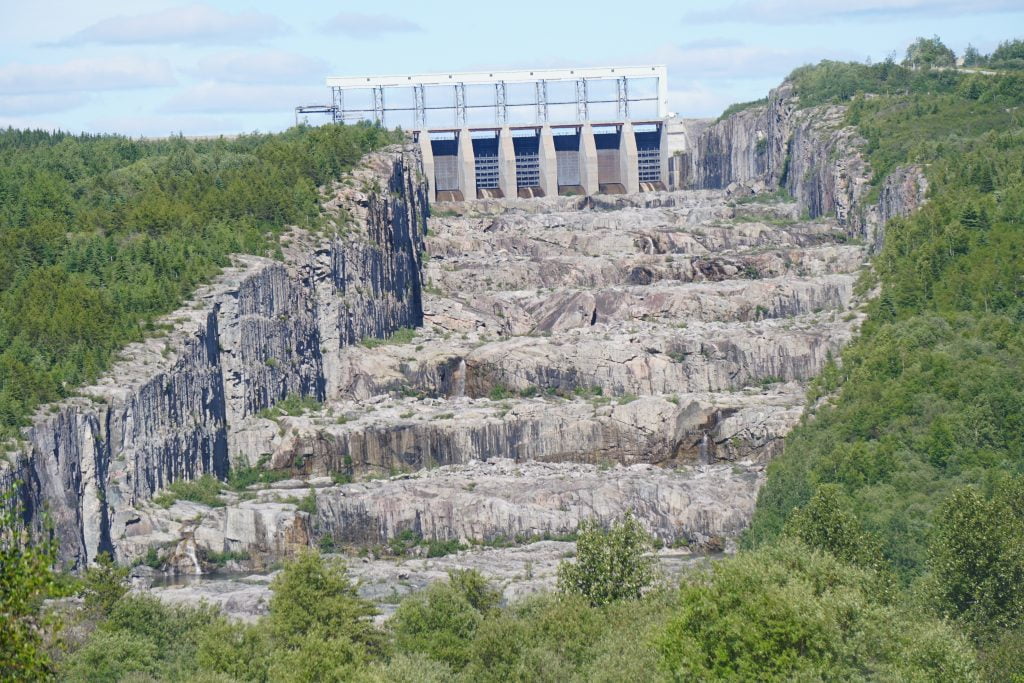

We fueled up and departed to see the 8th largest hydroelectric generating station in the world, the Robert-Bourassa generating station (or La Grande 2). The scale of this project is truly epic.

The dam holds back a reservoir greater in size than Luxembourg and is the largest body of water in Quebec. If every inhabitant on earth drank from the reservoir, each of us would have to drink 10,000 liters (2,641 gallons) to drain it. The structure is 53 stories high and has enough generating capacity to keep the lights on in Australia. You take my point of course – this was worth seeing.

We weren’t disappointed. We arrived at the entrance which was not staffed. So, we convoyed down the winding gravel road until we arrived at the viewing spot for the “Stairway of the Giants”. We battled the bugs and took pictures. The stairway is impressive. It is, literally, a huge cut through the wilderness measuring almost a mile long and dropping 36 stories. The channel has 10 “steps” ranging 30 to 40 feet in height and 417 to 656 feet in length.

We drove to the viewing platform and took pictures. We drove to the top, took pictures. We spied what looked like an observation tower a couple of miles away on a high point. We drove there and climbed the observation tower. The wind was steady and the view was forever. In one direction was green Taiga that rolled into the sunny, distant mist. The other direction were distant islands forever adrift in a simmering blue expanse. Between were huge rocky dikes that separate the two majestic immensities.

After a couple hours of touristy exploration, we got back on the road and headed to our destination . . . Chisasibi. Chisasibi is just over 60 miles west of Radisson and is the end of the road. Just a couple miles past town is James Bay, the southern extent of the Arctic Ocean.

It was Saturday evening. When we arrived at Chisasibi, it was quiet. This gave the impression that it was a town in hardship. A town that was clinging to existence. But we would find later, this part of the world takes their weekends with family. They don’t work or go to town.

We drove past the village and the final miles of the James Bay Road. The road abruptly terminates at a gravel beach with dozens of large freighter canoes resting in a long line, just above the high tide mark. There were covered shelters and some rustic campsites.

When we arrived, we had just finished what many would call, “a bucket list item”. We celebrated by walking into the ocean, taking pictures and surveying the vastness in front of us, nibbling at our accomplishment. We had journeyed 1,300 miles, as far north as roads would take us in eastern North America. But, we had just begun our expedition. It seemed like weeks since we left the urban sprawl of Michigan.

We pitched tents, gathered fire wood from Taiga and got ready to settle in for the night.

Just as we lit the fire, a pickup pitched and yawed slowing down the trail to our camp. The driver, a Cree, jumped out with a smile. I immediately asked who we can get permission to camp, realizing we had neglected this task. He said, “This is my land, our land, your land – you can stay here”, then he chuckled. His name was Robert and he was charged with watching the boats for the village. He was retired from a hydro company a number of years ago. His English was good, but still broken. He told us that he mostly spoke Cree. He was stopping to check on us because everyone was at Manoweedow (the gathering on the island).

We offered food from our meager supplies, which he accepted. He also accepted a seat at the fire. Upon biting into a sausage, he grunted his pleasure, showed me the sausage and asked, “What is it?” “Jalapeno and Cheese, I think”. He grunted again, “Good” and he chuckled, and held it for another 20 minutes before finishing it. He seemed to enjoy the coffee and cherries. We sat – nibbling, sipping and telling stories.

The conversation went on for almost an hour. This was our first contact with the Cree and it was a bit enchanting. It was almost like meeting an old friend. We talked about the modern world, the old ways, the history of the area and the changes that have happened over the past 40 years. We mentioned our objective of Cape Jones and his eyebrows arched, his eyes widened. “Long Ways. . . way up” he said.

Eventually, he had to depart or his wife would get worried. With smiles and wishes for a great life, he slid into his truck and pulled away.

I think we realized, at that moment, that we were about to make friends as if they were already old friends.

We had just arrived however, there was much to do, so we relaxed in the darkness, the fire glowed and the tide slowly drained from shore. We turned into our shelters for the night. Tomorrow, we would explore.

Written by Chuck Hayden