The Anishinaabe have utilized maple sap for centuries. The first written record of this antioxidant-packed resource had been in 1557. Last year, Michigan produced an impressive 200,000 gallons. Each gallon of this “liquid gold” is worth at least 15 times more than crude oil. Join us as we investigate the rich history, the dedication in processing and the community surrounding maple syrup. Did you know there had been a great maple syrup heist in 2012? Let’s go on an adventure in our North American woods!

Legends

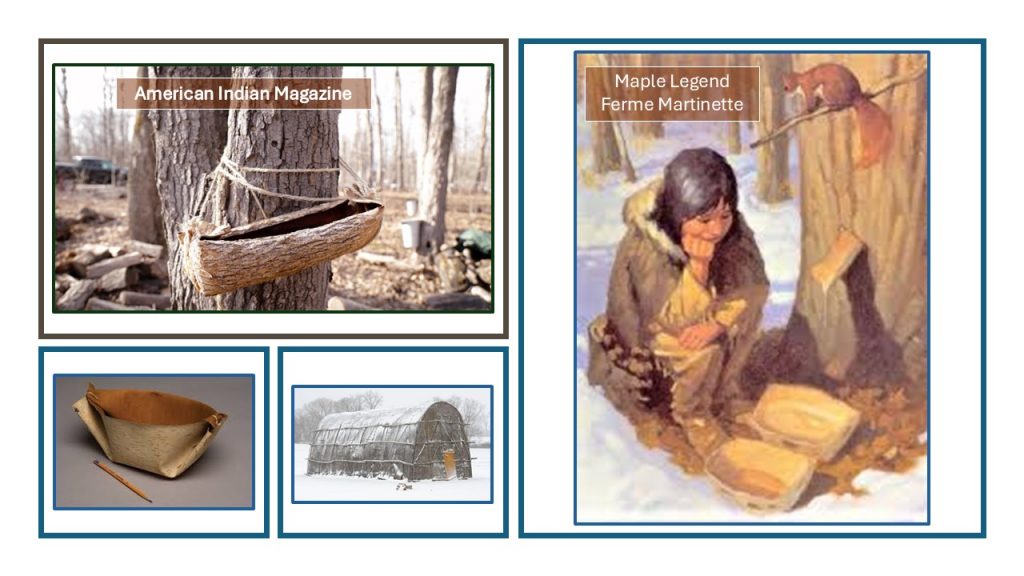

First Nation legends tell of the Iroquois leader, Chief Woksis, who had flung his tomahawk into a maple tree trunk after a long night. By morning, the sun had coaxed the tree’s lifeblood from its wound. The clear liquid dripped onto the frozen ground. His ever-practical wife (some stories say it was his daughter) tasted the sweet liquid and decided to cook their meat in it. This had been a revelation. The caramelized maple glaze was succulent.

Another Anishinaabe legend speaks of seeing a squirrel lapping up the sweet maple sap seeping from a small chewed hole. People tasted this clear liquid and began collecting it in birch bark bowls tied to trunks. This life-sustaining liquid soon became a staple in First Nation homes.

Eye Wash

Indian Villa Ontario

Imagine. It’s deep winter and the fire inside the Iroquois longhouse has created dense smoke. Eyes sting. A mother, or maybe a grandmother, retrieves a bowl of cool, clear liquid. It’s “maple water.” It’s thicker than regular water and comes from nearby maple trees. This fluid would be used to refresh one’s eyes from the burning sensation of smoke.

The First Written Evidence

Without written language, the native tribes hadn’t recorded their uses of maple sap. It wasn’t until 1557 when French explorer, Andre Thevet, had written about someone cutting down a maple tree which released “some kind of sugar, which they found to be as tasty and delicate as any good wine from Orleans or Beaune.”

Grain Sugar

The Anishinaabe refined methods to crystalize the sap into grain sugar which could be stored more easily than the maple water. The First Nations people had used both heat and freezing as methods.

Colonel James Smith, from the Jamestown settlement wrote about how natives used the freezing method to produce sugar. “Their large bark vessels, for holding the stock-water, they made broad and shallow; and as the weather is very cold here, it frequently freezes at night in sugar time; and the ice they break and cast out of the vessels. I asked them if they were not thawing away the sugar? They said no; it was water they were casting away, sugar did not freeze, and there was scarcely any in that ice. They said I might try an experiment, and boil some of it, and see what I would get. I never did try it; but I observed that after several times freezing, the water that remained in the vessel, changed its colour and became brown and very sweet.“

Photos taken at the Wittenbach-Wege Agri-Science Center in Lowell, Michigan.

As mentioned, boiling could be used to separate the water from the sugar crystals. Most believe that natives added hot rocks in the sap to evaporate the water. However, this could leave impurities in the sugar. Another hypothesis is that the natives would boil the sap in a newly cut and hollowed elm log. As the sap boiled and the tree’s moisture seeped to the ends of the log, it would carry the sugar with it. The sugar crystals would harden on the sides of the log. When it cooled, the sugar could be scaped off and stored in cone shaped birch containers.

Maple sugar had been eaten with berries, grains and even mixed with bear fat. They also ate plain cakes of sugar.

Cake Sugar

Tribe members would eat an estimated forty pounds of cake sugar from the end of winter until their crops began to grow. This would sustain them as they relocated to their summer camp and planted their gardens. Cake sugar was made from the crystalized sugar and sap put into wooden forms.

Todays “cake sugar” molds are usually in the form of maple leaves.

Maple sugar had been used in trade and given as gifts. Maple sugar had provided life-sustaining nourishment. It is filled with antioxidants: zinc, magnesium, potassium and calcium.

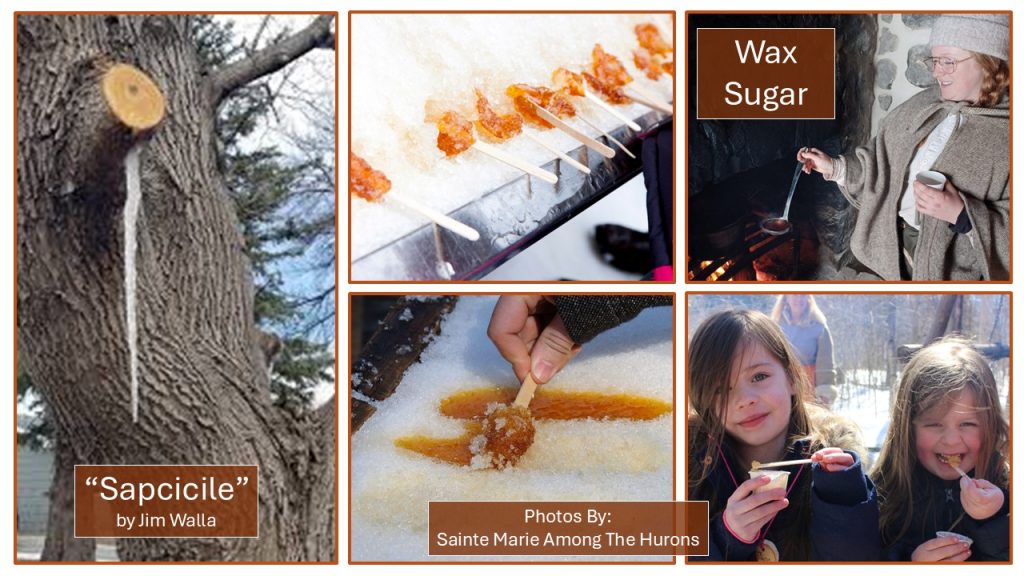

Wax Sugar and Sapcicles

On “sugaring days,” when sap was being boiled, ladles of the hot liquid could be drizzled over fresh snow and gathered on the end of a stick. This taffy-type treat, “Wax Sugar,” was enjoyed by children and adults alike.

Another timely treat that you can even find today are “sapcicles.” Frozen sap icicles can be found on frigid spring mornings. As a child, Chuck enjoyed these treats. Honestly, I hadn’t known about the magic of the maple tree until I was teaching second graders and took annual field trips to our local Wittenbach-Wege Agri-Science Center. So, I joined the classes for their excursion last week.

Second Grade Field Trips – Maple Sugar

Now some people seem quick to disparage public schools, but in our community of Lowell, experience-learning leads the way! This teacher has even learned a lot, too! As students’ eyes lit up at the magic, only maple trees can provide, my eyes misted over. This natural resource of maple sap has dripped into their awareness and they will always carry it with them.

In conjunction with the Lowell Historical Museum, students traveled among three stations learning these time-honored traditions. The Anishinaabe area included methods of making maple sugar, even tasting the large crystals. First Nation children had worked alongside the adults and would be rewarded with games that taught hunting skills which the second graders were able to enjoy, too.

After a hike to the cabin, youngsters witnessed the boiling of sap at an outdoor fire where homemade donuts were being cooked in an iron kettle. The ‘toothless-grins’ sampled sap over ice, a donut and a pickle. The pickle is a traditional treat during maple sugaring as the vinegar-tartness counteracts the super sweet sap.

Photos taken at the Wittenbach-Wege Agri-Science Center in Lowell, Michigan.

Understanding maple trees and how and why they produce sap was the third station. Each tree can produce between 5-15 gallons of sap each season. (Hold onto your socks for this!) It takes 40-50 gallons of sap to make one gallon of maple syrup. The tree needs a new tap each year. Students even made a “tree cookie” necklace nametag with colored beads representing the resources a tree needs to survive: water, sunlight, soil.

French 1600’s

The French explorers traveled down the St. Lawence Seaway into Canada. They sent scouts, called Envoys, to live with the natives, learning their language and survival techniques. The French had been used to and preferred pure, white cane sugar. They disapprovingly called the native’s maple product, “red sugar” or “country sugar.” Their frustration grew when they couldn’t devise a method to turn the crystals white.

Their attitude soon changed when importing cane sugar became impossible. The French employed their copper and iron kettles to boil the sap. The immigrants grew in appreciation for the sweet maple sugar.

When French surveyors arrived a short time later, they approved of the maple resource. They determined that it was healthy and even administered boiled sap as a tonic for “lung pains.”

Thomas Jefferson

A century later records show that in 1791 Thomas Jefferson saw the economic potential of maple sugar production. He had hoped to lessen the amount of imported cane sugar. Jefferson had a “maple orchard” planted at his Virginia estate, Monticello. Sadly, his trees had failed to thrive. In order to collect sap, spring temperatures need to dip below freezing at night and warm to at least 45 degrees Fahrenheit during the day.

Civil War – Tin Cans

During the Civil War mass production of tin cans made sap collection easier in the northeastern states, which had the proper climate for maple sap. With troops traveling across the country, customs and traditions were shared. Maple syrup grew in popularity.

Wooden Barrels – Collection

Wooden barrels revolutionized how maple syrup was preserved, marketed and transported. Today, tin and plastic jugs are used as well as plastic tubing.

Bottom Left: Pierre Rheaume Center: Colonial Williamsburg

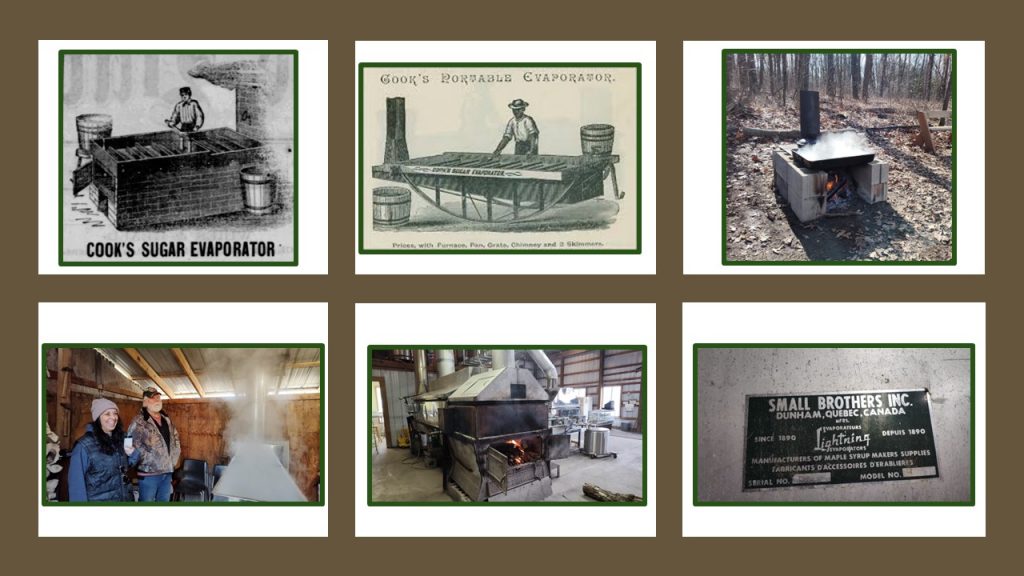

Evaporator Pans

Over the next few decades inventors perfected the sugar evaporator, an elongated pan with a crimped bottom which aids in speedier evaporation. The Small brothers patented their model in 1889 which still holds today! I was amazed to see the “Small Brothers, Inc. Patent” on Maple Hills Sugar Bush evaporator model! (bottom center and bottom right)

Quebec’s Reserve

For centuries the Haudenosaunee, Abenaki and Mi’kmaq peoples of North America have valued maple sap. When Canada gained independence from Great Britain in 1867, they chose the maple leaf for their country’s flag.

(Grab onto your socks again!) As recently as the year 2000, The Quebec Maple Syrup Producers (QMSP) established a 94,000 barrel reserve. The facility stretches over an area equal to five football fields. The six million pounds of maple syrup is worth an estimated $18 million dollars!

With grade A syrup trading at about $32 per gallon, that adds up to $1,800 per barrel, approximately 15 times the price of crude oil.

This reserve is kept in a secure, heavily guarded location near Quebec. With 2/3 of Quebec’s annual exports (86 million pounds) coming to the United States as well as supplying sixty other countries, “The Global Strategic Maple Reserve” keeps the prices balanced, even if there’s a poor production season.

The Great Maple Syrup Heist

Monday, July 30, 2012 had been a sticky day when Michel Gauvreau, an accountant for The Quebec Maple Syrup Producers, discovered that more than 9,000 barrels in the syrup reserve were filled with water. Someone had stolen the syrup!

That day new security measures were being put in place. A task force began researching the black market for maple syrup. Twenty-three people were arrested, but one-third of the stolen syrup, worth $18.7 million, was never recovered.

Recently a fictional series, “The Sticky” has aired on Netflix with Margo Martindale and Jamie Lee Curtis. This is loosely based on the great maple syrup heist.

Not only does maple syrup hold economic importance for nations, but it has brought communities together for centuries. This labor of love includes hours of Herculean effort: chopping wood for the fires, collecting sap daily, boiling it down and then bottling it. Each step is endless repeated for several weeks each spring.

The Community Surrounding Maple Syrup

As we strode the wooded path Chuck pondered, “Even today, across the backroads of Michigan and Quebec, the smell of woodsmoke and boiling sap drifts through the air. This ritual, generations deep, where neighbors swap stories over steaming cups of fresh syrup, poured straight from the evaporator.”

“But lately, there’s been a bitterness that has nothing to do with burnt sugar. Thanks to tariffs and trade wars, a quiet mistrust has started to simmer between Canadians and Americans. The old friendship, once as reliable as the spring thaw, feels strained.”

“But here’s the thing, if the two nations could sit down, stoke the fire and boil down some syrup together, we might remember that its not us causing the turmoil. It’s the suits, the handshakes in boardrooms, the politicians throwing up walls where there should be bridges. Out in the sugar shack there’s no room for that nonsense.”

Thank you for joining us. Stay tuned for a Restless Viking YouTube video on our caper investigating the food that changed the world, Maple Sap. Keep being curious and make memories with your people.

Resources:

“Discover Five Amazing Facts About Canadian Maple Syrup” article by Athena McKenzie February 17, 2025

“The Story of Maple” article and video

Coombs Family Farm website

Maple Trader website

“The Liquid Gold Reserve” January 2024 article

Atlas Obscura Gastro Obscura article

“The Story of Maple” video

American Indian magazine article

Maple Syrup Made How article

Maple Syrup Production Facts article

The History of Maple Syrup article

The History of Maple Products video

Sticky Gold article by Brendan Borrell January 9, 2013

Maple Sugar Candy recipe

4 thoughts on “The Food That Changed The World – Maple Sap”

I enjoyed reading this piece, Poppins! Best regards.

Thank you, Jim. Best wishes to you!

Great job???? in sharing such a Sweet???? Part of History which I am sure at times can become Very Sticky. In all seriousness, Thank You Both for Your hard work in bringing to us all so many Wonderful Adventures. Question????! Did Da Viking get any of the Maple Syrup in his Beard ?⚓️

Hahaha! Nope, but Poppins drizzled some syrup down the front of her shirt.