Along Michigan’s scenic “M22,” near The Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes, stands Point Betsie Lighthouse. First lit in 1858, it is the oldest structure in Benzie County and still serves as a United States Coast Guard automated aid to navigation. Point Betsie’s history stretches over 167 years. Who were the “Wickies?” Why is there a grave marker on the property? Were you aware that they have haunted tours in October? Did you know you can stay overnight or even host a wedding here? Join us for a peek into some stories of this historical fixture.

Photo Credit: My North article

Our Stop Along M-22

Lake Michigan’s waves roared and crashed as we strolled toward the Point Betsie Lighthouse. The white caped water has always made me wonder about the early people who had survived here, traversing this wild water in crafted canoes. Then, over the following centuries, Europeans made advancements in shipping. But, what about the families who’ve lived in this lighthouse? What would that have been like?

Retracing the footsteps of lightkeepers, known as “wickies,” Point Betsie lighthouse gave us a peek into the perpetual work it had taken to tend this mariner’s beacon.

How Did Point Betsie Get Its Name?

French explorers had named this spot, “Pointe Aux Bec Scies,” which means “point of sawbill ducks.” These diving birds have narrow beaks with serrated edges. Englishmen later contrived “Point Betsie” from the French moniker.

When Was Point Betsie Lighthouse Built?

It had been 1852 when the Great Lakes lighthouse superintendent had decided the southern entrance to the Manitou Passage needed to be marked with a guiding light.

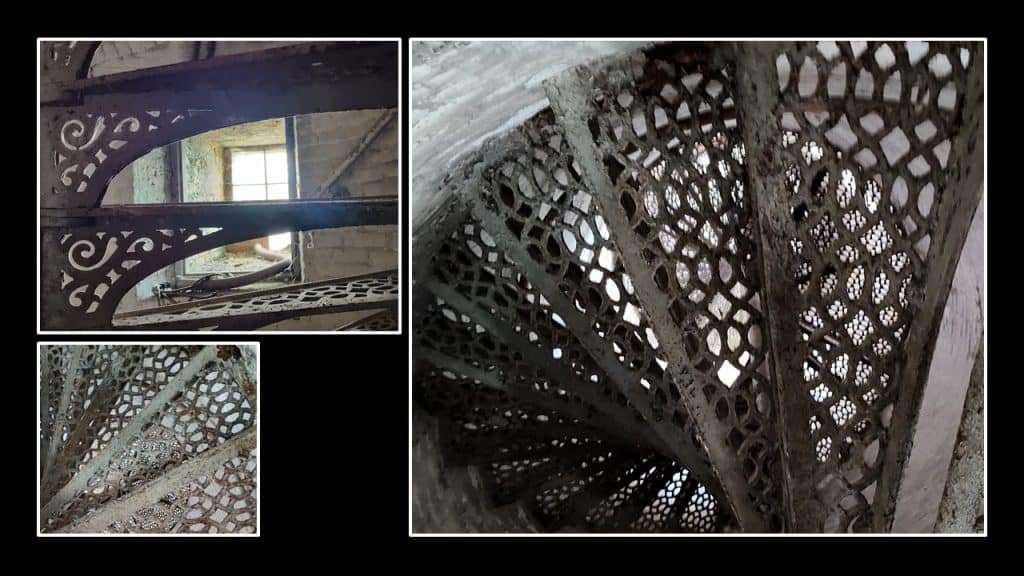

Point Betsie Lighthouse construction had started in 1854 and continued for four years. Finally, in 1858 the fourth-order Fresnel lens was lit. This 39 foot tower stands on a dune, putting it 52 feet above Lake Michigan. This warning light is visible for ten miles and still used today.

Photo Credit: Benzie County Historical Society (left)

The erosion of sand had caused the foundation to need repairs the very next year. A concrete apron was added to the base of the tower to prevent further erosion. Then in 1900 an addition was made to the two-story keeper’s dwelling, attaching the tower.

Who Were The “Wickies?”

The first “wickie,” David Flurry (1859), was soon followed by Able Barnes (1859-1860). Each “wickie” had stayed less than a year.

Point Betsie “wickies” had lived in the keeper’s quarters and lit the oil lamp wick, keeping it burning through the dark hours. As well, they maintained the oil basins. You see, the lamp would consume 5.25 ounces of oil hourly, so the light needed routine refilling. The lighthouse lamp needed to burn from dusk until dawn every. single. night.

The clockwork mechanism turned the prisms so the light would show as a fixed white guide with a flash every 90 seconds. The soot from the burning oil collected on the cut glass. Cleaning the delicate prisms of the Fourth Order Fresnel lens had been an important daytime task, too.

After just months, this perpetual work as a “wickie” had sent David Flurry and Able Barnes seeking alternative employment.

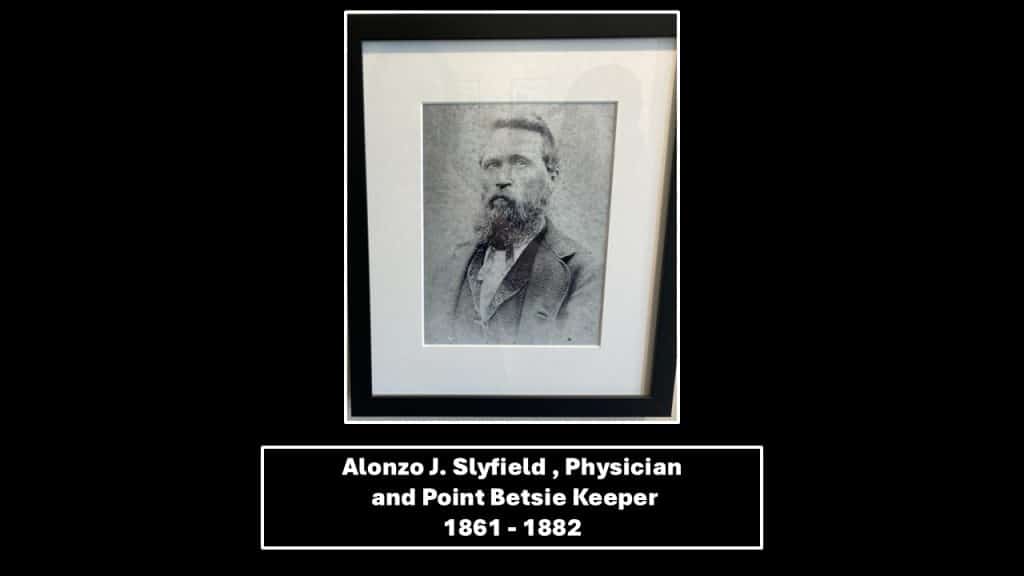

Alonzo and Alice Slyfield

Then, in September of 1861 Alonzo and Alice Slyfield relocated from South Manitou Island Lighthouse along with their three surviving children: Ella, Charles and Edwin. Sadly, Mary had recently passed away due to illness.

While towing an additional boat of supplies, the family rowed their way across Lake Michigan to Point Betsie. The family remained at Point Betsie for twenty-one years.

During those long nights, the responsibility of keeping the light burning often fell on Alice. Alonzo had often been been away serving as the community’s doctor and coordinating life-saving missions in the dangerous waters.

Alonzo and Alice’s family grew by three more children during their time at Point Betsie: Elmer, George and Jessie. By the time their youngest daughter, Jessie, was born in 1871, Alice had already become a grandmother.

Their oldest, Ella, and her husband, Charles, had a baby in 1870. Ella and Charles had lived nearby keeping house for an elderly widow.

Flour Barrels

Due to currents, items were often pushed up on shore near Point Betsie. During the Civil War (1863), barrels of flour floated ashore. Apparently they’d been thrown from a passing ship which had run aground. The shoreline had been littered with water-logged containers which would need to be repacked. The Slyfields and their neighbors repacked the flour, which numbered 100 barrels. This valuable staple kept the area families sustained during the dark days of war.

Captains Helped The Wickies

Alonzo and his sons fished regularly, salting their catch and waving down passing steamers to haul their bounty to sell. Grandson, Charles Slyfield, had written “They (steamship captains) knew keepers had no other way to ship anything.” Keepers always had to stay at their light station every. single. night.

So, the steamship captains’ kindness had been a life-line for the keepers. The captains would haul the “wickies'” barrels of fish, sell them, buy supplies from a list written by the keeper and return with the keeper’s requested items.

Life Saving Rescues

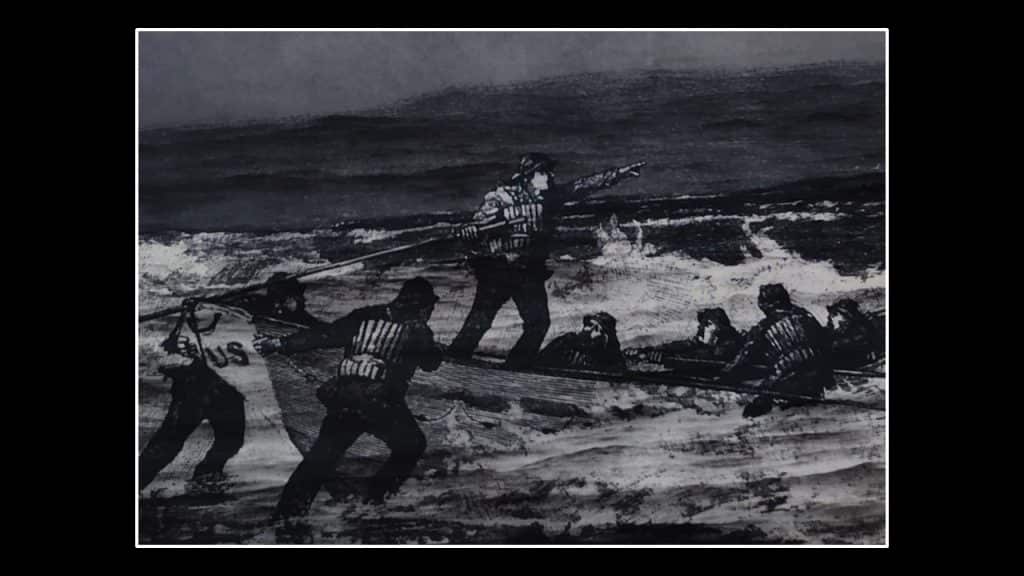

When a boat crew found trouble, “wickies” had been the first on scene. These keepers and their families assisted those in peril and sometimes had to rally nearby residents to assist in life-saving rescues.

On a brisk October morning of 1871, a man arrived at the lighthouse shore, dressed in dripping undergarments. Alonzo, Alice and the family warmed the sailor by the fire, dressing him in layers of dry clothes and giving him a hot meal.

The man told of two schooners which had become grounded. One 4.5 miles north and The Comet, a mile north of the lighthouse. On shore, local men came together for this rescue mission. They tied lines to a small, flat-bottomed skiff. This lifesaving vessel was dragged to The Comet where crew members climbed aboard in pairs and were pulled to shore. The task filled every hour of the day as the slate-gray sky swirled with rain clouds.

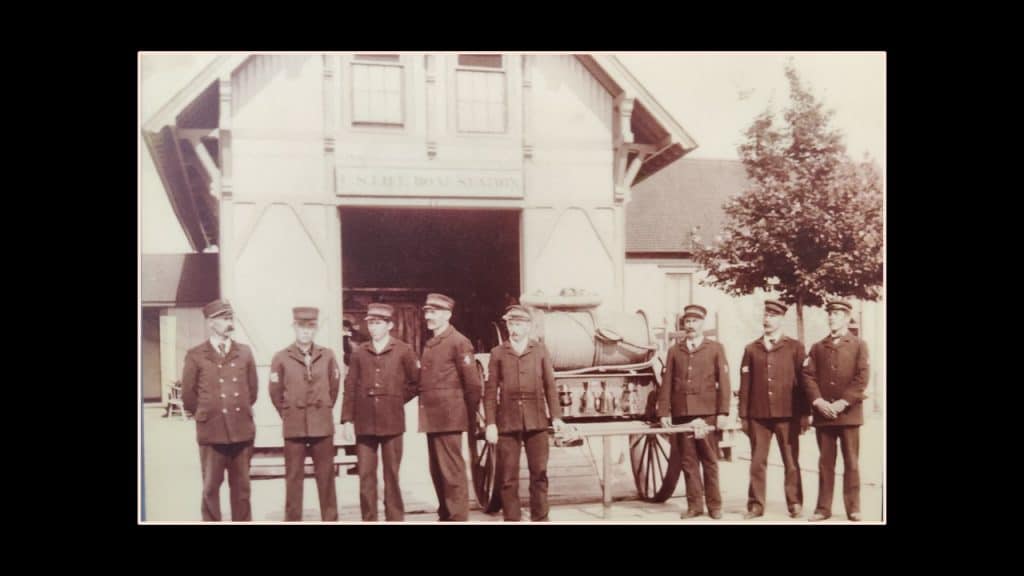

Life-Saving Station

This heroic mission had been the first of many recorded life-saving tales. It had served as a catalyst for building a life- saving station, constructed four years later alongside the Point Betsie Lighthouse. Surfmen manned the shoreline and performed daily drills preparing for more missions.

These brave surfmen were the beginning of the United States Coast Guard

with the motto is, “Semper Paratus,” which is Latin for “Always Ready.”

Benzie County Historical Society

One of Many Surfmen Rescues

Photo Credit: The Point Betsie Museum

It had been a late November night in 1898 when the St. Lawrence steamer ran aground two miles from the lighthouse. Gale-force winds and hail pelted the ship, crew and the rescuers. The surfmen knew their daily practiced protocols wouldn’t work in this snowstorm, so the captain directed a different route. These surfmen, clad in cork jackets, pursued the recovery of fifteen souls from the vessel, bringing them to safely to shore. The Point Betsie museum quoted, “It was one of the most innovative and dangerous rescues in U.S. Life-Saving Service history.”

“Wickies” Keepers and Assistants

After decades of lighthouse tending, Alonzo retired in 1888. His son, Edwin, stepped into role of the Point Betsie “wickie.” Alonzo and Edwin had served in a long line of over 30 keepers and assistant keepers providing a guiding light for ships passing Point Betsie.

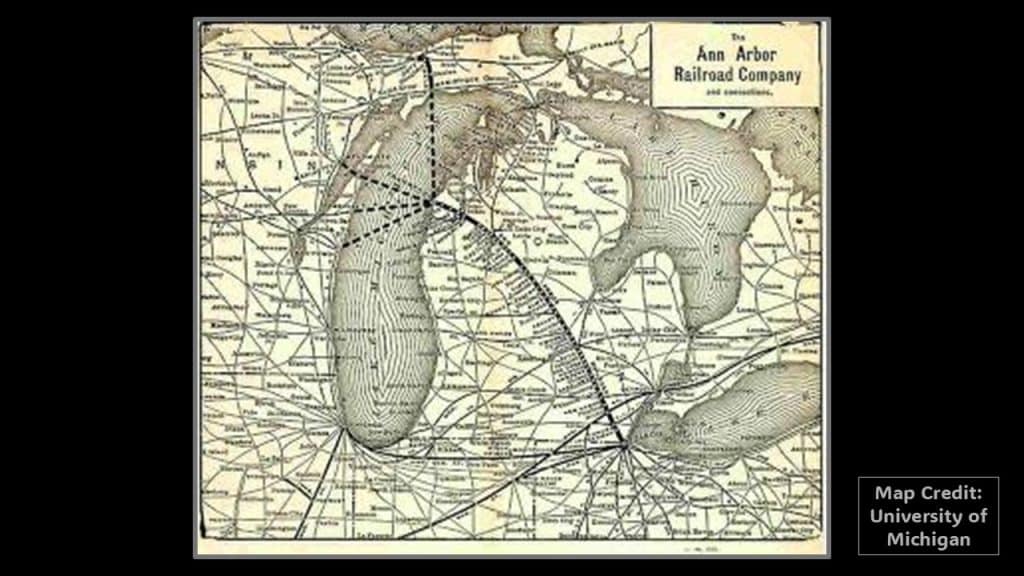

The Ann Arbor Railroad

Just as Edwin Slyfield had stepped into the role of Point Betsie’s keeper, the Ann Arbor Railroad began crossing Michigan with service between Toledo, Ohio and Frankfort. This rail line began to change the scope of travel in 1889 as shipping had been significantly slower and started to fall out of favor.

Fog Signal Building

A couple of years after Edwin had taken over, a fog signal building had been constructed in 1891. The bright red structure houses fog horns which sounded for 4-6 seconds every two minutes.

By 1921 electric air compressors powered upgraded twin Type-G horns.

Today, the building stands silent, proudly nodding to a job well done.

An Assistant Keeper / New Lens

With the extra duties of the fog horns, an assistant keeper was assigned to Point Betsie in 1892. The keepers’ house had been expanded and made into a duplex, housing the two families.

At that time a newer model Fourth Order Fresnel Lens had also been updated. This flashing light replaced the solid beacon which had only flashed every 90 seconds.

Surfmen = U.S. Coast Guard

The brave surfmen at the Life-Saving Stations had been the precursor to our United States Coast Guard. By 1937 the USCG had been developed, so the Life-Saving Station at Point Betsie had been decommissioned.

Electricity

Back in 1921 electricity was installed at Point Betsie. With an electric air compressor in the fog signal building and lightbulbs in the tower, keepers could relax a little. However, the Manitou Passage has always had dangerous currents and shoals, so this lighthouse has remained vital to mariners.

The last keeper retired from Point Betsie in 1963. That has made Point Betsie the last manned light on the Great Lakes. Full automation didn’t take place until 1983. Then, in 1996 modern optics replaced the Fresnel lens. Point Betsie continues to be an active aid to navigation today.

Friends of Point Betsie

Benzie County took possession of the property in 2004. Efforts to renovate the interior and exterior took years of extensive effort. In 2014, at 156 years old, this light station opened to visitors. The “Friends of Point Betsie,” a non-profit group, assist in upkeep and host tours.

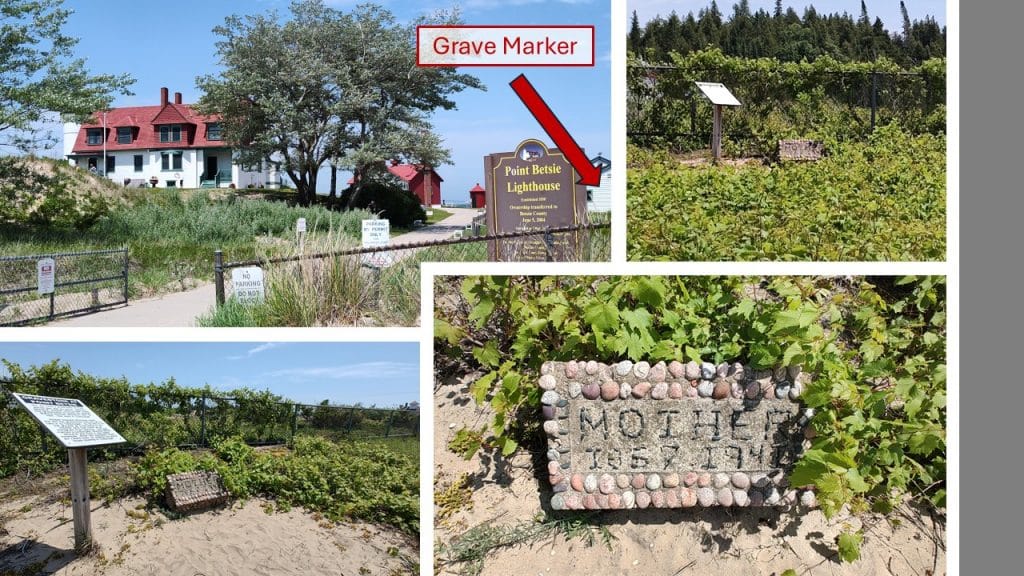

Why Is There A Grave Marker?

Among lush ground cover, a mosaic of stones stands off to the side. A small sign watches over this monument which reads, “MOTHER 1857-1941.”

The story of this mysterious grave marker starts in the late 1800’s when Martha Madsen Wheaton came to the Great Lakes as an immigrant from Norway. She had married lumberjack, Andrew Richie Wheaton. They lived in the upper peninsula until her husband’s untimely death. With six children, the widow moved to Cheboygan on the northeastern side of the southern peninsula to work as a domestic house cleaner.

One of her six children, Edward Wheaton, became a keeper at Point Betsie (1934-1946). Sadly, when his mother passed in 1941, Edward was unable to attend his mother’s funeral in Cheboygan, so he constructed a stone grave marker to honor her.

When Edward was finally able to trek across the state, he couldn’t lift the monument into his car. So, the marker is now a permanent memorial to his mother, Martha Madison Wheaton 1857-1941.

Stays, Haunted Tales and Weddings

Did you know that people can stay overnight in the keeper’s quarters? They are taking reservations for 2026. There’s enough space for six in this one of a kind hotel. Here’s the link!

Weekends in October have tours where seven haunted tales are shared. They are scheduled on October 17, 18 & October 24, 25 between 6:30-10 each night. For $15.00 you can retrace the steps of the “wickies” and hear spooky stories about the lighthouse! Here’s the link!

The Point Betsie Lighthouse is a unique wedding venue, too! Check out their information for making your wedding memorable.

Stay Curious and Keep Making Memories

Related Links:

Watch our YouTube video of this trip!

“Life-Saving Stations: Unsung Heroes” A Restless Viking article

Arcadia Marsh Nature Preserve, along M22, is a treasure. Here’s the Restless Viking article.

Here’s another article about an M22 site, The Mill in Glen Arbor!

The Oldest Spring in Michigan, “Old Faceful” Restless Viking article

Resources:

Point Betsie website

United States Coast Guard website researched by Melissa Buckler

My North article by Carly Simpson

Lighthouse Friends “Point Betsie” article

Fly in Flynn Media video

Benzie Area Historical Society

A Brief Sketch of the Life of Charles Slyfield by Julie H. Case excerpts

Julie H. Case is the great-great- great granddaughter of Charles B. Slyfield.